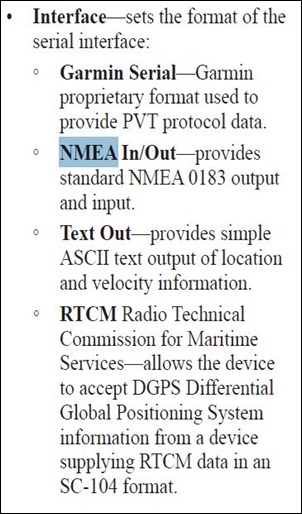

Continuing on from Part I yesterday, today I’ll look at the interface on the Garmin 62s, and how it displays and handles maps.

Interface

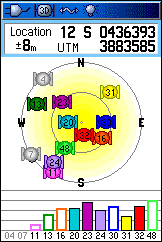

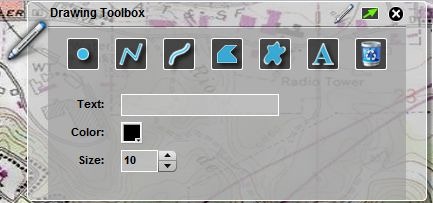

I absolutely hated the touchscreen interface on the Oregon 450t I reviewed last year; doing even simple operations like creating a waypoint took multiple screen presses and changes. With the hardware buttons on the 62s, most of my objections no longer apply. A single button press can create a waypoint, and you can switch between different information screens (satellites, map, compass, trip info, waypoints, tracks) with just a few button pushes. Info screen order can be customized to show only a few screens, or all 24 available ones. You’re giving the option of flipping through full info screens sequentially, the default on my older Garmin 60Cx model, or using Garmin’s new Page Ribbon interface, which pops up a scrollable horizontal list of the info screens available, so you can jump immediately to the one you want:

And you can set up multiple profiles with different sets of info screens and other configurations (tones, interface, units, etc.). This is a big step up from my old Garmin 60Cx, with only one profile configuration, and makes using the unit far more flexible.

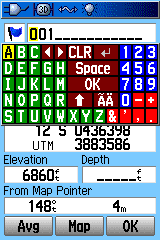

The one downside to the 62s’s interface compared to the Oregon series is that inputting letters/numbers is easier with the Oregon’s touchscreen interface; with the 62s, you have to use the cursor pad to scroll across a keyboard to select individual characters. Even so, they’ve improved the keyboard dramatically from the old 60Cx and eTrex version, by expanding it and making separate keyboards for letters, numbers and symbols:

Garmin 60Cx keyboard |

Garmin 62s keyboard |

You can switch between different keyboards on the 62s with the buttons at lower left/right, or use the In/Out zoom buttons. While it’s not as easy as a touchscreen, it’s still not bad. Overall, the 62s interface is a substantial improvement from that on the 60Cx; two thumbs up.

Maps

Newer Garmin models, like the 62s and Oregon/Dakota/Colorado series, support both vector and raster map data.

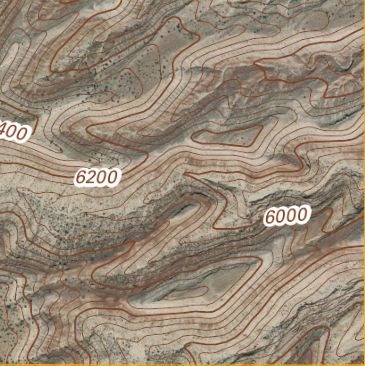

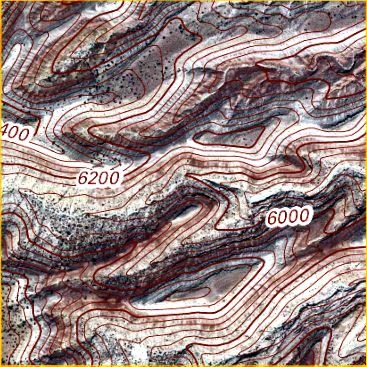

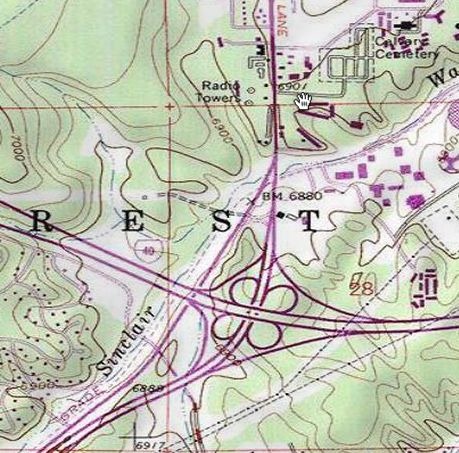

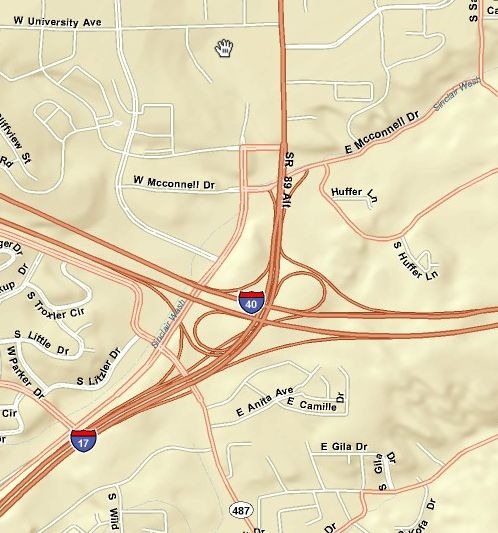

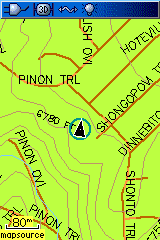

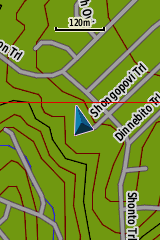

Vector

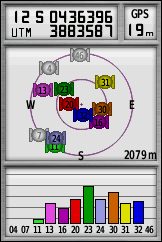

There’s no denying that the Garmin vector map ecosystem is bigger and better than for either of its main competitors, DeLorme and Magellan. There’s a wide variety of map types available for purchase from Garmin, and any old mapsets you currently have will also work on this system. I have an old Garmin Roads and Recreation mapset from 1999 that still works fine on this new model; comparable Magellan mapsets from the same era either don’t work, or require complete reformatting. What’s more, they’ve modified the map styles on some maps to make them much easier to view. Compare these screenshots of the same topo map view from an old Garmin 60Cx and the new 62s; the maps on the 62s are much easier to view, especially in daylight conditions:

Garmin 60Cx |

Garmin 62s |

Having said that, the base 62s comes only with a very rudimentary basemap installed, and you’ll really need to get additional maps to get full use out of it. Compare that with DeLorme PN-60 model, which comes with a full US road and topo mapset (1:100K equivalent); or the newer Magellans, available with a full 1:24K-equivalent topographic map covering the entire US. Garmin really needs to start including better map data with their base units, if they want to stay competitive.

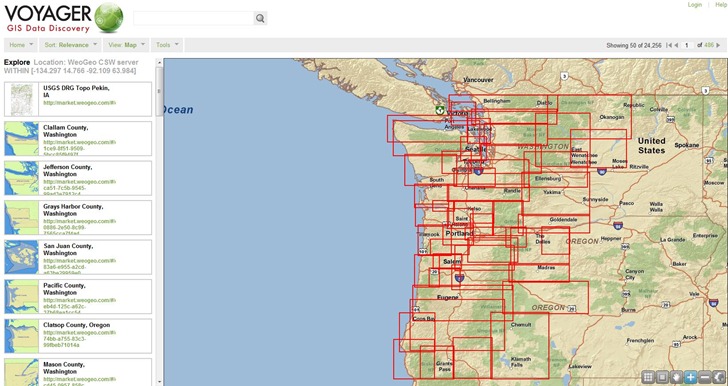

The 62s is also fully compatible with most custom vector mapsets created by hobbyists over the years using free or cheap tools; see my series on Garmin vector map tools for more info. These include all the 1:24K-equivalent US topo maps at the GPS File Depot site, which are completely free and of comparable quality to Garmin’s paid (and expensive) equivalents. Getting vector map data on a DeLorme requires their xMap software, which I believe is available for new purchasers of PN-series models like the PN-40 and PN-60 at a discounted price of $150. Magellan really doesn’t have any comparable legitimate capability; there are some people creating custom vector maps for Magellan units, but you have to use pirated software and a convoluted process to create them.

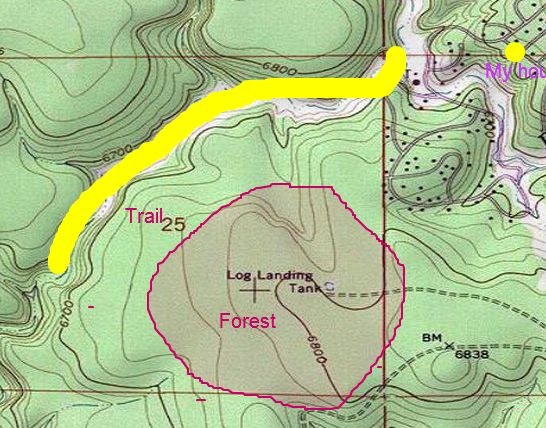

Also supported are custom map types, where you can redefine symbol sets for points, lines and areas to whatever you want. Excellent examples of what can be done with this capability are available in the New Jersey section of the GPS File Depot maps; Boyd has used this custom styling to create vector maps that look very similar to USGS raster topos. One exception to custom map type support are the vectorized raster maps generated by my Moagu utility; these take advantage of hardware quirks specific to the older 60Cx/60CSx models, as well as some eTrex models, and these quirks have been removed from the newer Garmin models. However, vectorized raster maps created by programs like MapWel or BMap2MP work quite well on the 62s (as well as Oregon/Dakota/Colorado models). My Moagu utility has a GUI front-end for BMap2MP with settings optimized for USGS topographic maps; these maps display almost as quickly as raster Custom Maps versions (more on this below), without Custom Maps’ restrictions on map size. Using this approach, you could get several dozen USGS topo maps at full resolution on a 62s or comparable newer Garmin unit, versus 6-8 using Custom Maps. Below is a screenshot from a 62s showing a USGS topo map creating using BMap2MP with the Moagu GUI and optimizations:

Raster

The newer Garmin models can support raster imagery, like scanned maps and aerial photography, directly. There are two ways to get this kind of imagery on a Garmin unit.

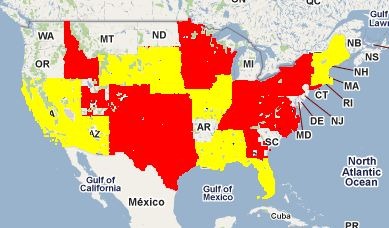

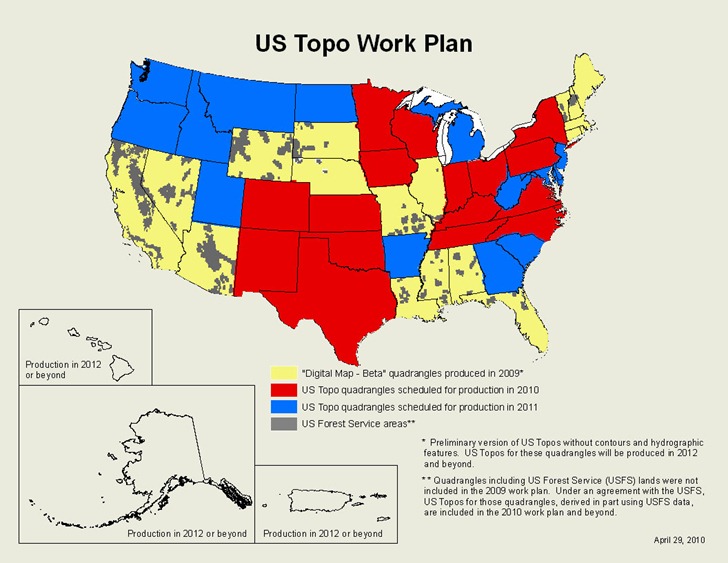

1. Garmin has a subscription service for world aerial imagery, called BirdsEye Imagery. For $30 a year, you get a subscription for unlimited downloads of aerial imagery (and nothing else); Garmin claims sub-meter resolution, but my local maps appear to be at about 1-meter resolution, and I’ve heard people in countries outside the US complain about poor data for their area. Download map data requires that you have Garmin’s BaseCamp software installed on your system, and a compatible Garmin unit connected to your computer. You can download sample data in BaseCamp, covering about one square kilometer, even without a subscription, so that you can check it out before buying it. Map data expires when the subscription expires. At least for my area, the aerial imagery is pretty good:

However, Garmin’s subscription service falls well short of what you can get from DeLorme’s comparable subscription service. DeLorme offers not only aerial imagery, but also USGS topographic maps and marine charts, for the same $30 subscription price. They also offer a separate subscription to Digital Globe satellite imagery, which offers 30-cm resolution across the world. You can also get Garmin BirdsEye topographic maps for some European countries, but it’s a la carte instead of subscription; $30 buys you up to 600 sq. km of topographic maps like OS maps for the United Kingdom; sounds like a lot, but it’s only an area of roughly 25 km x 25 km on a side, which really isn’t that big. On the other hand, Magellan has no comparable subscription service.

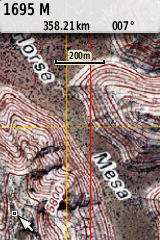

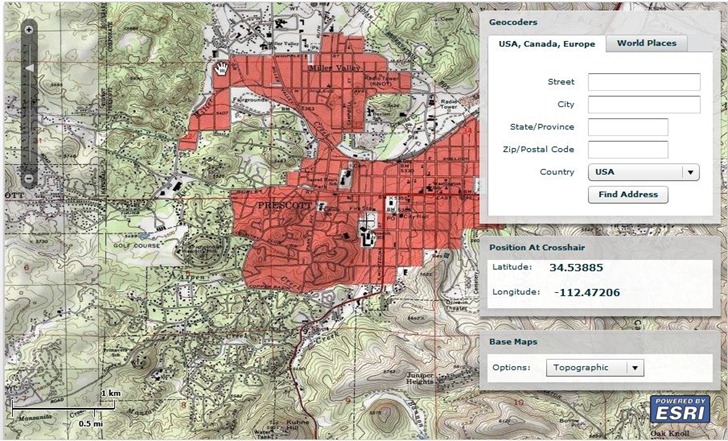

2. In October 2009, Garmin added a new feature to the Colorado/Oregon/Dakota/62/78 series called “Custom Maps”. You can take a scanned map or aerial photograph, calibrate it in Google Earth, then export it as a KMZ file for viewing on your GPS unit; here’s an example:

It’s a nice feature, and it’s great that Garmin added it for free, but there are issues:

a. The maximum image size you can create is about one megapixel; larger images will have their quality automatically degraded. You can get around this limitation using programs like G-Raster, mapc2mapc or OKMap, which can chop a larger image into smaller subtiles that meet this size restriction.

b. A bigger problem is that there’s a maximum limit of 100 raster image tiles that can be viewed on a Garmin unit. Many people have asked Garmin to increase this limit, but so far Garmin hasn’t done so. They claim that it’s due to performance issues, but I have to believe that’s nonsense. It should be trivially easy to modify the unit’s software so that only maps in your current location were active, or to give people the option to disable/enable Custom Map files using the unit’s map manager, but Garmin hasn’t implemented either of those. I suspect they’re afraid that people will use Custom Maps instead of their BirdsEye subscription series, but given the extra steps required for Custom Maps, and convenience of BirdsEye imagery, I don’t really see this as a valid reason, especially on a unit as expensive as this one.

And BirdsEye imagery currently only includes aerial photography for the US, and not other commonly-desired raster imagery like topographic maps; if they’re not going to expand the range of imagery offered by that service, why not give users the ability to add as much of their own imagery as they want? As someone who was using my Moagu software to vectorize raster maps for Canada told me, Garmin’s BirdsEye service does them no good if it doesn’t offer the maps he needs, and Custom Maps doesn’t help if the total number of maps he wants on his unit exceeds their limits. There are people out there trying to reverse-engineer Garmin’s BirdsEye format so that you can create your own maps using that format, without the limitations of Custom Maps. But since this requires modifying your GPS unit’s firmware, and possible violations of the DMCA, I’m steering clear of that option.

By contrast, DeLorme’s xMap software lets you put any raster imagery you want on their PN GPS models (as well as GIS vector data like shapefiles). While it’s expensive at $150 (with a PN purchase), the combined cost of the most expensive PN model (PN-60) plus xMap software is comparable to the price of the 62s alone. So if the ability to put any maps you want onto your GPS is a requirement, you might want to give the DeLorme units a serious look. There are ways to put custom raster imagery on newer Magellan units, but they’re not exactly user-friendly yet.

Map management

You can install maps onto the 62s and similar models using Garmin’s old warhorse software, MapSource. However, Garmin seems to be slowly de-emphasizing that software in favor of their free BaseCamp program and its map installation utility MapInstall. I think MapSource is far easier to use for managing maps, but BaseCamp is better for managing tracks and waypoints, and is the only option for download BirdsEye imagery. However, MapInstall doesn’t let you save mapsets the same way MapSource did; every time you want to upload certain maps, you’ll have to select them manually.

The newer Garmin models do offer some major feature upgrades from older models in the way they handle maps:

1. Older models could only hold up to 2025 total map tiles; the new models can handle up to 4000 map tiles. This is, of course, not mentioned in the manual.

2. With older maps, there was a single map file generated that had to be called “gmapsupp.img”, otherwise the unit wouldn’t recognize it. And uploading a new set of maps erased the old set. If you upload maps to the newer Garmins, the same gmapsupp.img file is created. However, if you put the unit in mass storage mode and then rename the map file with a different name (but the same .img extension). the unit will still recognize it. This has some major advantages for map management. For example:

a. Upload all the topo maps for a state to your Garmin unit; the map file will be named gmapsupp.img.

b. Rename that gmapsupp.img file to something descriptive, e.g. az_24k.img.

You can now upload another mapset to the GPS without erasing the first one, something impossible on older Garmin units. You can also copy this map file from your GPS to your computer to archive it, and then delete it on your GPS unit to free up memory space. If you need these maps again,you don’t have to go through BaseCamp or MapSource to install it again– just copy the file back onto your GPS in mass storage mode,and the unit will automatically recognize it. This is an incredibly useful feature that is not mentioned in the manual.

3. Older Garmin units could only use microSD cards for storage up to 2 GB. Garmin says that the new limit is now 4 GB, but that’s a bit misleading. The maximum .img file size that can be created is 4 GB, but you can have multiple 4 GB .img files on a single card; people have reported using a 16 GB microSD card without problems. I’ve only used 2 GB, so I can’t confirm this. This is, of course, not mentioned in the manual.

4. Finally, thankfully, the new models use USB 2.0, up to 480 Mbps; older models used USB 1.1, painfully slow with large mapsets at 12 Mbps.

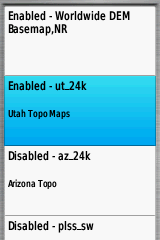

The map manager list is also somewhat improved from the older units; you now get full mapsets better defined, and easier to select:

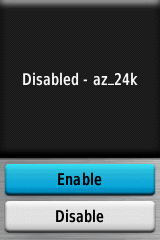

From this list, select a mapset to enable or disable it; this includes not just vector maps, but also BirdsEye imagery and Custom Maps. There is one serious annoyance with this process, though. If you select a mapset by scrolling and pressing enter, that doesn’t enable/disable it directly; instead, you get a screen asking you if you want to Enable/Disable that mapset:

Attention, Garmin – a mapset is either enabled or disabled; there are no other options. So why not just enable/disable mapsets by selecting them and pressing enter; why do you require people to go through an extra screen with Enable/Disable options?

So far, for the topics I’ve covered in parts one and two (hardware, interface, maps, GPS reception), there have been pluses and minuses to the 62s, but on balance, I’ve had a pretty positive view of the 62s; the only major exceptions have been the expensive price, pathetic manual/documentation, and unreasonable restrictions on Custom Maps. But in Part 3, I’ll look at the way the 62s handles waypoints and tracks, which is a huge disappointment. Plus, I’ll wrap things up with my conclusions and recommendations.